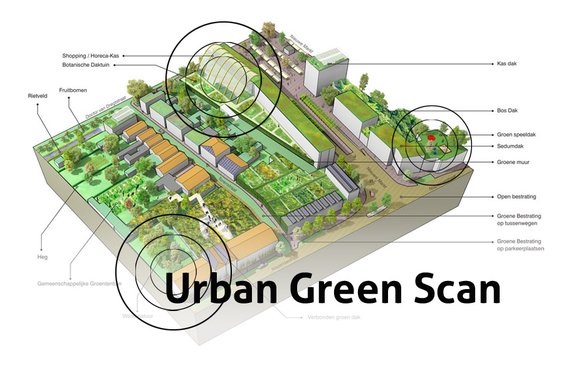

Urban Green Scan

Service > Mapping the opportunities for beneficial green in your city

We hear a lot about it: the integration of green spaces could change our cities from dead concrete caverns to lush green paradises, with reduced pollution, local food production, and many social and health benefits. But how to achieve this in specific cities is less clear: where exactly do these opportunities lie, what is possible, how do we communicate it, and where do we start?

This service answers exactly those questions and provides guidelines for your city for establish a greener, cost effective environment.

The Challenge

Usually, the desire to “green” our cities is driven by a collection of small bottom-up initiatives. While these can be effective at times, without the backing of policy and project development they’ll stay just that: small scale and locally confined. Some of the largest positive benefits of including natural areas occur only on a neighborhood or city scale.

Ultimately, when only small, local projects are realized, the major benefits of a green city will not materialize. Some cities have central policy guidelines for urban “greening,” but what that exactly means is often not clear. Who does what, and where can which intervention provide the most positive benefits? Do we choose green roofs, green facades and walls, permeable pavements, or just an apple tree here and there? Where does urban agriculture fit in?

It’s time to do something about that.

With a multidisciplinary team of ecologists, architects, urbanists, and local policy makers we made a map of opportunities for beneficial green interventions for the Dutch city of Roosendaal. We analyzed the city on three scales: building, neighborhood, and the entire inner city. Another scale can also be added to connect these urban initiatives with regional greenspace plans. For each scale, we identified all possible green interventions, from house plants to interconnected rooftop gardens.

We created a comprehensive chart that shows what kind of intervention can be applied in each type of location, and what its specific benefits will be. Finally, these natural elements were placed on maps of the city at the three different scales to show where many opportunities exist. The provided document shows this part of the process. The next step is to find stakeholders for each intervention, using the document to show the beneficial aspects of each section. This way city council, communities and enterprises can actively start to green their city together.

Communication

This opportunity scan shows the importance of connecting natural spaces in our cities. One of its most important functions is to provide a clear and inspirational guideline to city inhabitants for what they can actually do. From residents to small business owners all the way to city government and large project developers, the map lays out a multitude of opportunities for “greening” that will result in more beautiful, cleaner, safer, and better functioning places, usually saving money along the way.

A starting point, tool, and method

The Urban Green scan can serve as the defining starting point for the city’s multi-scale effort to phase in nature as a powerful beneficial asset. The map can be updated easily to reflect new situations. It can be used by the city’s residents as a tool for finding local opportunities for greening.

Meanwhile, the supplied methodology document shows other cities how to do the same kind of analysis in their own area. Well-integrated natural areas offer more benefits than almost any kind of other intervention; from improving city life to assisting in climate mitigation and adaptation efforts. As Roosendaal greens its inner city using the map, we hope that other cities will use this set of tools as a starting point to follow suit.

Examples

Sustainable Office Interior

To demonstrate that a sustainable office interior can be exciting, affordable, and very practical we decided to make our own work space an example of just that.

The Except office in Rotterdam is located in a restored office building, which had previously stood empty for over a decade. Our renovation process brought together new ideas about collaboration, innovative material use, and exciting design.

RGD Building Portfolio Scan

The RGD manages and maintains all the real estate for the Dutch government. In such a large portfolio, a large number of buildings are suboptimally used. We developed a scan to analyze a specific object, identify potential beneficial uses and plot out a redevelopment plan.

Wesleyan University Teaching Museum

Except designed a new type of museum used for teaching with four distinct collections of artefacts, musical instuments, and prints, located in the center of the Wesleyan University Campus.

The museum has been designed for longevity, with a possible life span of over hundreds of years. Its main quality is its ability to change function over time while remaining a high quality environment for a variety of purposes. It’s flexible, exciting and features solid passive energy systems that continue to work through the ages.

Maasterras Sustainability Scan

This project explores opportunities for sustainable development in the planning, policy and urban design of a large urban district in Dordrecht, the Netherlands.

Boston Fort Point Masterplan

This urban redevelopment project of the Fort Point district in Boston, MA proposes a unique strategy to reduce city-wide traffic congestion, increase livability and property values and contributes significantly to the resilience of the city as a whole.

Sustainable Schiebroek-Zuid

We developed a sustainabile conversion and development plan for the post-war social housing area Schiebroek-Zuid in Rotterdam. The project provides a flexible and exemplary roadmap for converting the neighborhood into a self-sufficient and sustainable area. It applies innovative energy solutions, urban farming, social and economic programs, secondary currencies, and adaptive redevelopment strategies.

This project was commissioned by housing corporation Vestia and agricultural research network InnovatieNetwerk.

Merredin Health Industries Spirulina Plant

The Merredin Spirulina plant, developed in the year 2000, is one of the first projects in which we applied systems thinking and our holistic, systemic approach to innovation, using ecology as a main component.

The result is a highly unusual but stunningly effective business case for a sustainable, ecological industry to revive a desert town in Australia.

This project is a testament to the strength of holistic, systemic approaches. For this reason, we documented the project extensively on this page, indluing the conception process, business case and design of the plant. For more detail, feel free to contact us.

Roadmap to the BGI Manual

Blue Green Infrastructures (BGI) increase the resilience of urban and rural landscapes, integrating their core functions with natural features and processes. Hurdles exist in the process of translating BGI-related knowledge and data from science to practice, and a tool that facilitates this transfer is still missing. We conducted a research in collaboration with a team of partner organizations (JNCC, IFLA Europe, BiodivERsA, and NRW), to pinpoint key preliminary knowledge to design such a tool, and collected our key findings in a report downloadable on this page.

Contact

Tom Bosschaert

Director

+31 10 7370215

+31 10 7370215